|

|

WAITING

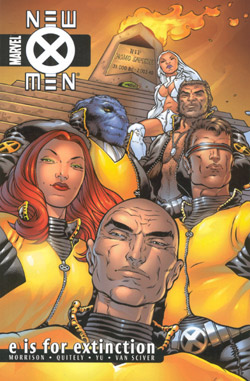

FOR TOMMY: ETHAN VAN SCIVER

By

Richard Johnston

I first came across Ethan Van Sciver's work on Cyberfrog

years ago, when it seemed the colour indie boom was about

to do what the B&W indie boom did earlier. Cyberfrog was a

frenetic, action-packed tale of an amphibian cyborg and it

certainly made an impression on my young eyes. Since then,

Ethan has made a name for himself on superhero work, keeping

that same energy but finding more subtle ways to express it.

His recent work on New X-Men gave him prominence, as has his

devil-may-care attitude about what he says and who he says

it about on internet message boards. A natural for Waiting

For Tommy you might think. You might think right.

RICHARD

JOHNSTON: If you could take young Ethan, about to start

work on Cyberfrog, what advice would you give him? And how

much of it would you think you'd have listened to?

ETHAN VAN SCIVER: I'd have listened to anything I would

have said to myself. I always have.

I was about 19

when I started Cyberfrog. I came from a very large and very

poor Mormon family, and my mom and dad were divorcing right

at the moment I got involved with Harris Comics. We lived

in South Jersey at the time, and they both decided to live

far away from home and each other. Harris Comics literally

became my family at that point, and the excitement and awe

of getting paid to do comics was as close to a band-aid as

possible for having a fresh broken home. And the money was

better than anything I'd ever seen before. So I was absolutely

miserable and angry and happier than I'd ever been, all at

the same time. I was travelling, meeting professionals, and

having books published and read by comic book fans.

If I

could go back now, I would tell myself to stop buying up all

of those horrible toys with the money I was making. TOY BIZ

and Star Wars was not the answer to finding a lost childhood.

I wish that money had gone into the bank. Also, I would have

found a collaborator to write Cyberfrog with me. But circumstances

being what they were, I don't have too many regrets. Things

turned out okay.

RICHARD:

You're talking to a man sitting opposite a row of Clerks toys

so... what do you make to the nostalgia boom that's been erupting

through comics over the last few years? Another symptom of

the same problem?

ETHAN: I guess so. To be honest, I haven't thought

much about the nostalgia boom (which seemed more like a whimper

to me) in that light. I suppose I believe that this generation

is the first one to really want to hold on to the things of

their childhood, and not place such a high value on growing

up. Which is fine with me.

In my own case,

it was the mere fact that I was the second oldest of nine

children, and therefore, I didn't get any toys. I would get

a few Star Wars figures, C3PO over and over again, but it

hurt somehow that I didn't have what the other kids had. When

I was very small, (and this is utterly pathetic) I would take

the backs of the cards that the Star Wars figures came packed

on...remember how they used to have a big shot of all of the

individual figures that were available there? Well, I'd take

a pair of scissors and cut them out, one by one and play with

them. I think I wanted to buy toys for that kid, the kid that

had to do that.

RICHARD:

Oh that brings back memories. well you're a big boy now, and

have put aside foolish things. Or so it seems. How have you

found the internal politics of both Marvel and DC? You've

worked/are working on Impulse, Flash, Wolverine, New X-Men,

all of which have attracted attention, publisher/editor/creator

conflict and general unease in their time, while being quite

an outspoken individual. How does a creator cope at a time

when other people on the project are divided?

ETHAN: I've said before that I prefer the "internal

politics" of DC, and that's pretty much how I feel. Marvel

feels chaotic to me. Maybe that comes through in their product,

and perhaps that's part of their appeal. But I'll be absolutely

upfront here. I went to Marvel to work on New X-Men the same

way a young man joins the Marine Corps. It wasn't really something

I wanted to do, but it was clear that I needed to do it to

take that next step in life. I had conversations with the

editors I had established relationships with at DC beforehand.

They were a terrific support. Although if I had stayed at

DC following IRON HEIGHTS, I probably could have done almost

anything, I knew, and they were good enough to agree with

me, that working with Grant Morrison on X-MEN would finally

break me out. I told them I'd be back, shortly.

I had NO interest

in X-Men. It seemed like a relic out of my childhood that

I didn't care to return to. I also didn't really care to work

with Grant Morrison, since I had a longstanding rule that

I'd only work with writers that I was on equal footing with.

The writer and artist should serve each other, that's how

good comics are made. When the scales are unbalanced, things

don't feel right in the book itself. Nevertheless, on to war.

DC had given me lots of self-confidence. And so did the fans.

Within the first

few weeks at Marvel, I was dealt a devastating, ugly and underhanded

blow when I was shown the private email of Grant Morrison

to X-Men editorial regarding my work thus far on the series,

over the charade of being taken to lunch. I had been told

that the work I was doing was 'lovely, and Grant was very

impressed by it'. They didn't have the balls to tell me what

was really going on, and so they sat me in front of a computer

to read 'Grant's brilliant plans for Cyclops', which turned

out to be something completely different. I learned through

the email that no less than three other artists were chosen

by Marvel Comics to fill in on the title, without Grant's

consent. I was the fourth, and he was very unhappy.

You've got to

understand, this sort of tactic was utterly ALIEN to me. I

wasn't prepared too be lied to by my bosses like that. I wasn't

used to being kept that much in the dark about how my writer

was feeling. Usually, I correspond with them. And here I was,

three weeks into a two year exclusive contract and this sort

of sh*t was what I had to look forward to.

Frankly,

I couldn't draw anymore. I would sit at my table and just

stare at it, convinced that I had no talent, no hope, and

had been swindled away from a situation where I had been creatively

flourishing. But I had a family to support. I wrote a stammering,

apologetic email to Grant, telling him I wasn't aware of what

was going on, and I would happily quit if that would be better.

He wrote back the sweetest, most sincere letter to me expressing

sympathy for me and rage at them for invading his privacy,

and said we'd be fine working together. I never told Joe Quesada

what happened. I didn't know if he knew or not, and I figured

it'd be better if I kept it to myself.

Pages:

1 | 2

| 3 | 4

Continued Here...

|

|